Interview Between Julia Ferrari and Toni Ortner for Write Action Radio

Ortner: Good evening. This is Write Action, and this is your host, Toni Ortner. This is your community radio station, WVWLB in Brattleboro. 107.7 FM. You can stream us on the web at WVW.org. Before I begin today’s show, I’d like to say the views and opinions expressed on our program are those of the hosts and the guests, and as you know, not necessarily the radio station. We have several sponsors I’d like to thank, and that is the Outlet Center, Twice Upon a Time, The Vermont Jazz Center, and did I say the Outlet Center? I’m happy to be with you today. It’s a beautiful day. The sun has been going in and out, and downtown here on Main Street, the light on the old buildings in Brattleboro is illuminating the cornices where there are incredible designs on buildings that are just not built the way they used to be. There’s no question about it. And it’s a wonder to look at these brick buildings that stand on the street in downtown Brattleboro. It honestly feels like you’ve moved into a painting by Edward Hopper. So we have a number of things I’d like to announce. There are some upcoming events I’d like you to be aware of. We have the Brattleboro Film Festival, which begins on the 31st of the month and goes all the way to the 9th. And you can go online to find out what films will be shown. And the Boston Gay Men’s Chorus will be at the Latchis Theatre also on November 1st. So again, welcome to the Write Action Radio Hour, and we have a very unusual and special guest tonight and her name is Julia Ferrari. So welcome to the show, Julia, and thank you for driving down to Brattleboro.

Ferrari: Hi Toni. And hello to Brattleboro.

Ortner: Okay, I’d like to tell you a little bit about Julia before we begin the interview and she reads some of her own work. Julia is one of the most revered letterpress masters in the world today. Her work is in museums and private imprint collections. There’s a picture of her online smiling next to President Obama and you can also find her online on Wikipedia, Facebook, Twitter, the blog of the Press, and VermontViews.org. In the middle of 2012, Julia Ferrari became the sole proprietor of the Golgonooza Foundry and Press after the premature death of Dan Carr, who was her lifelong husband and business partner. You can imagine what that felt like. Nevertheless, Julia is determined to carry on and continue the Press on her own. At the moment, Julia has an intern. They’re going through standing forms to inventory them and creating a book to document the Letterpress’s projects from the past 30 years. That is how long this press has been in existence. Her Press has translated and produced Broadsides and poetry books and is currently – She is currently binding and making copies of a special book called Reach of the Heart, which is a combination and a collaboration of Dan Carr’s poems and Julia’s own original artwork. There are and have been several recent exhibits. One of them was called The Whole Art of Language, which appeared at the David Walters Gallery right here in Brattleboro. And there’s a huge fabulous current exhibit that Julia may tell us about if we can get her.

[Laughter]

Ortner: Because there’s so many questions I’d really like to ask her. In addition, Julia happens to be a phenomenal writer. I do the old lady blog at VermontViews.org and of course, I do look at the other columnists and that’s how I found Julia’s work. She wrote a particular piece as part of her column about what she was experiencing going through the entire grief process and I was very touched, deeply touched, and startled by the depth of her honesty and what she revealed. In fact, I was in tears and even tonight, reading it again when she asked me what section I’d like to read, again, I found myself in tears again. But of course, one can’t be tearful on the radio. So Julia, again, welcome to the Write Action Radio Hour.

Ferrari: Thank you, Toni.

Ortner: And can you tell us, how did you get involved in hand-letterpress printing? And what does that mean for those readers who do not know what that means?

Ferrari: Okay. Well, I got involved in 1977 in Boston. I went to the shop of my, you know, eventual partner, Dan Carr and there was this art being created there and its letterpress printing. Dan was a poet and I was writing poetry at the time and he had an ad in the real paper that said, “Come print your own poetry.” And I saw it and I said, “Okay, I want to do that. That’s pretty cool.”

Ortner: This was in Boston, did you say?

Ferrari: Yes, in Boston. And it changed my life. So it was the beginning of a path that I would never have guessed I would have gone down, because I was not – Although I was writing poetry, I never thought about designing or, you know, book design or anything like that. Graphic design. It was not on my radar. And Dan was just part of the Press. It was an amazing place to be. There were a lot of people coming in as apprentices at that time. I was one of, like, 70 people.

Ortner: 70?!

Ferrari: Yes. A lot of people.

Ortner: That’s amazing.

Ferrari: And two of us stuck. Me and Mark Olsen, who was another apprentice. And we stayed with letterpress printing to this day. Both of us. Mark is now down in North Carolina. So that world opened up for me and I started seeing type and letter forms and design in a whole different way.

Ortner: Tell us a little bit about the process. I mean visually. What it looked like, for an observer.

Ferrari: Well, letterpress printing is the form of printing that is basically a relief process. So like a woodcut or a linoleum cut. You ink a surface and then the paper gets laid down on its surface and whatever’s on there gets transferred. So with letterpress, it’s actually words and letters. Generally in metal – when we were doing it, it was all metal.

Ortner: Could you have different pieces for the alphabet and the different typefaces?

Ferrari: Yes, it’s all individual pieces of individual letters that are assembled into a poem. And we were part of this small press movement back then in the late 70s. When poets couldn’t get published.

Ortner: Absolutely. What was the name of the Press at that point?

Ferrari: Four Zoas Press.

Ortner: I remember reading about the Four Zoas Press because I was running Connections Magazine in New York City at the time and there weren’t many presses that were publishing women. And that’s why I remember the name. Four Zoas from so long ago.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: What did that mean, Four Zoas? Where did that title come from?

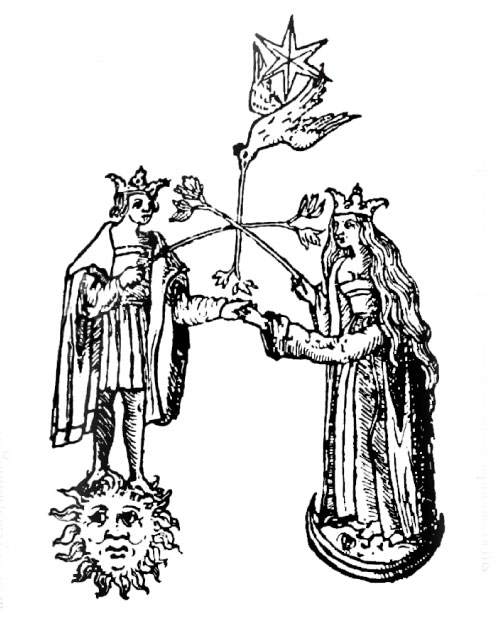

Ferrari: Well, Four Zoas is from William Blake and William Blake, of course, independently, was an inspiration for both Dan and myself. Because he was a poet. He was an artist and printed his own works and made books. He and Catherine, who we, you know, don’t give as much credit to but it was actually Catherine and William Blake together as a team. And so, the Four Zoas was an epic poem. A sort of – I think it was never finished, but it was this amazing mythology. And so it was the Four Zoas Press, which existed before me. Before I came into the Press. And then when I came in, myself and Mark Olson, we started doing some chapbooks together as a team, the three of us, and we called it Four Zoas Nighthouse.

Ortner: Why did you call it the Nighthouse?

Ferrari: We were working at night. It was sort of the Boston division. The Press started out in Ware, Mass. Hardwick and Ware, Massachusetts.

Ortner: And then there was the Boston division. And were you doing chapbooks at the time?

Ferrari: Yes, all chapbooks.

Ortner: What were some of your others – and did you do your own chapbook at the time?

Ferrari: Yes, we did, let’s see, some of the authors. I think I did a small, like, a Broadsides and things. Dan had chapbooks. Some of the authors were Terry Ottman who actually lives in Vermont now. We had, let’s see, Morgan Gibson, who I think lives in Tokyo now. Or maybe in California, was in Tokyo for a while. Mary Crow, who’s now out in Colorado. A lot of people at that point in time, who are still writers, because I’ve communicated with them because of the show that’s down at Mass Art and let them know that, hey, some of your Broadsides and your chapbooks are actually up. And they’ve written back to me.

Ortner: And are there any photographs? Can our listeners go online to see the show now, you said at the University of Massachusetts?

Ferrari: Yes, Mass Art actually.

Ortner: Mass Art?

Ferrari: Mass Art on Huntington Avenue.

Ortner: Mhm. And what website can they go to to see some pieces of the show, perhaps?

Ferrari: Well, let’s see. My blog has a few photographs, I think, yes it does. It’s GolgonoozaLetterFoundry.com. It’s spelled G-O-L-G-O-N-O-O-Z-A. Golgonooza.

Ortner: So we can see photographs there?

Ferrari: You can see a couple photographs there, and at Mass Art, I think if you go to their main page, you can at least see information about the show.

Ortner: Tell us a little bit more about the show. You must be very excited to have such a large show.

Ferrari: I feel lucky. It’s a 30 –

Ortner: Well, I wouldn’t call it exactly luck.

[Laughter]

Ortner: Discipline, talent, perseverance, courage, a lot. But not just luck.

Ferrari: Yes. Well, I feel gifted, I guess to be able to be there and –

Ortner: Blessed.

Ferrari: Yes. And so it’s a 30 year little retrospective of the Press. So it’s 10 years in the Boston years, a few years in Boston, and then – actually, it’s been 30 years in New Hampshire, so it’s a 30+ year retrospective.

Ortner: And we’re still in our twenties? How did that happen?

[Laughter]

Ferrari: Well, I was like, in my mid-, early-twenties in Boston when I stumbled into the Press, into the door of the Press.

Ortner: I’m just curious. How long does it take you – How long did it take you to go through that process of working with an associate and even print out one chapbook? And how long were those chapbooks? I know now chapbooks are like 30 pages. It must have been shorter then.

Ferrari: Yes, they were a little shorter, because were hand setting at the time. So it was all hand processes. I would say 15, you know, 16, 17, maybe 20 even sometimes, but we’re counting both sides of the sheet.

Ortner: I see.

Ferrari: And they would usually have soft cover bindings.

Ortner: And how long did that take to even do one, a few hours working a night?

Ferrari: Yes. Well, oh, it would take a couple months, at least. If we were working at night. You know, setting the type and then printing it. And we were just – you know, it had original art so it took some time to make the art.

Ortner: Now was that your art?

Ferrari: For a certain amount of books, once I came into the Press, it was my art. Because I came in as an artist, really. I was writing some poetry, but I was an artist. And so I started doing woodcuts and linoleum cuts as soon as I arrived because that was my interest.

Ortner: So your woodcuts and linocuts are in some of the chapbooks, and are those on exhibit right now?

Ferrari: At Mass Art, yes.

Ortner: At Mass Art. And how long will the exhibit last for?

Ferrari: Mid-December.

Ortner: Oh, that’s a very good amount of time. Tell us more about the exhibit and how it came about.

Ferrari: Well, the director of the library – it’s in the library. At Mass Art. And up on the 12th floor. And that school is a school – an art school – and a wonderful, challenging, place for students. And the acting director came to Brattleboro, lives in this area, came and saw the show at David Walters, and asked me to put a show up at Mass Art. And so it’s that show expanded.

Ortner: Serendipity or…?

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: As Young would say, synchronicity.

Ferrari: Good synchronicity. Good, wonderful connection out of that original show here. And I kind of made use of that show. I would meet people there and it was – there’s an article in a magazine called Design Traveler and that woman came up – she likes to go to anything related to printing. She’ll go and talk to people and interview, so she interviewed me there at that gallery. At Davids here in Brattleboro. So you can find that if you Google “Design Traveler Julia Ferrari.”

Ortner: So if you go to “Design Traveler Julia Ferrari?”

Ferrari: Yes. You can find it – it was Women’s History Month and it was – I believe it was done in March. So it was great. It was a good article and it was just wonderful to have that connection in town. Because I got to go there and meet people.

Ortner: Is this the first time that you’ve had the opportunity to really show the public what the Press has done for the last 30 years?

Ferrari: I would say it’s – it certainly is some new territory and ground there. It certainly is, for me alone, to do that. Before that, everything, you know, any shows we had, would be – You know, Dan and I were a part of. And we did do things here and I think we had a thing that happened – We went to a conference in Greece and things in England but that was with my partner. So this is different. This is very different.

Ortner: That must feel very, radically, different.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: To take that on alone, I mean.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: And also very necessary.

Ferrari: It has a different significance. It’s kind of an honoring of that time, that working time together, and yet it also is a point – almost like in writing – when you write something and you want to put it into print. Because that signifies a movement in time that is now concrete. It’s concretized. And you’re moving on and you’re writing new things. That’s how we used to think in the Press. If you wrote something, you wanted to get it into print, so that you could, you know, set it in type and print it so that you could –

Ortner: Let it go?

Ferrari: Let it go. Yes. And in a way, I think that having these exhibits is a way of not so much letting go, but moving into the next phase. So I’m moving into a new phase in my life by necessity. Because I lost my creative partner. My marriage partner. My business partner. All those things were wrapped up in one.

Ortner: That’s very, very unusual. You know, I was reading a book recently by – I’m trying to think who it was – It was a spiritual psychologist. And he was saying that marriage as it was as an institution where a woman was financially dependent on a man and did housekeeping roles and raised children is almost going out of our culture and what’s coming in as we move toward a higher level of spiritual development is partnerships between men and women that are soul partnerships where each knows that they are together in order to help each other rise up the ladder of spiritual development. And they stay together as long as that’s necessary with great compassion, empathy. And there are very few relationships I’ve seen in my life that are like that. Most are more like the old fashioned marriages, filled with a lot of pitfalls and conflicts and stuff, but very few love relationships that are the two souls working together. When you write – when I read that column, that you wrote in VermontViews.org, I think that’s why tears ran down my face: because I could see that it was a spiritual partnership. It wasn’t an ordinary marriage. It was a really spiritual union where you’re working together to create something that would have a legacy for future generations. It wasn’t just something that was a transitory thing, you know, over the present moment.

Ferrari: Yes. Yes, I would say that – that is very true, that there was a bond that was a creative bond that was really important and it was about opening up to the sort of – there was a connection to the world somehow.

Ortner: Well, it is connected to the world on an interesting level. It’s not just today. This moment.

Ferrari: Right. And because it’s print, and it’s poetry, and it’s – it’s part of the arts, in the world. There’s that inspiration to open the hearts, I think, of not only the writer themselves but to the reader.

Ortner: Oh, absolutely. I mean, I don’t have a TV, so I’m continually reading and I was reading a book – began to read a book – recently this week called Surrendered by Chang-Rae Lee, who’s written an incredible amount of books in such a full sea. And this book, Surrendered, begins in the Korean War and it’s about a young girl who’s caught in the war and the suffering she goes through. Part of me – I read about 100 pages and then part of me said, “This is so painful, this is so difficult; I can’t bear what she’s going through.” But then as I was driving along – I put it down for two days – I realized I wanted to know what happened to her as she grew up. I really felt that she was almost a real person. And in spite of the pain of what I had read, she suddenly seemed like a person, a friend almost, to me. And I really wanted to continue learning about the life of a character in a book! So I’m returning to the book. But when you said, “It touches the heart,” that’s a very interesting thing that you were publishing, both of you, publishing writers who you felt did touch the heart and tried to open up the hearts of readers. That’s very different from just reading some work that’s just very clever and ‘in style’ and light and ‘with it.’ It’s a very different thing. But the books the words that open up your heart are the words that – they’re imprinted in your soul. You remember them. You turn to them. You want to open that book again. Read the line again two years later.

Ferrari: Well, it’s a way of the world standing still in some way because –

Ortner: Absolutely.

Ferrari: I think the words could be written –

Ortner: And don’t we want it to stand still?

Ferrari: Yes. At any time. Yes, you could read something in the future or now and it would hopefully still do the same thing, meaning open the heart. Whereas something witty is not going to be necessarily witty in, you know, in the future. You know, it’s just –

[Laughter]

Ferrari: You know, it’s more current and – but the heart is a constant, somehow, I think, for all of us. And has depth and that was what we were interested in in the Press. There was that interest. So for me now, there almost a feeling of responsibility.

Ortner: I can imagine there would be. To carry on the work.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: That you began. Not to let it go.

Ferrari: Right. Yes.

Ortner: And it’s so much, I can imagine, how, you know, it’s like – I look around and I see couples and I say, “Even if they have a difficult relationship and they’re arguing with each other, there’s still two of them to make the meal. There’s still two of them to manage finance.” It’s very different to be alone, and then, to be in some kind of artistic endeavor, like running a press, where you were accustomed to having this person you loved as your partner and business partner and associate, almost like another hand. It must feel like a hand is almost cut off because the weight of it, which was evenly distributed, is now no longer evenly distributed. So it’s a very different – it takes a different kind of energy level because there’s nothing, no one to fall back on but yourself.

Ferrari: Yes, and I had a flood this Summer.

Ortner: Ah!

Ferrari: And that was – that really showed me how, you know –

Ortner: It can be frightening.

Ferrari: Yes, it made me aware I was alone, it made me aware of, you know, stepping up, and I – and not giving up, actually. Because –

Ortner: Were you sweeping the water off the floor? I remember doing that in the basement.

[Laughter]

Ferrari: Well, it was 18 inches of water in my basement –

Ortner: [Gasp] Couldn’t sweep that off.

Ferrari: Yes. And it felt – it did feel mythic. It felt like, oh here’s the flood, you know, that – but I always – I look at things as if they – there is some other meaning or sort of significance behind it. And I mythologize things. So I’m thinking, “Okay, the flood, you know, the sort of, the thing that sort of changes and takes everything away before the next thing.” And I said, “Okay, well, luckily nothing got ruined.”

Ortner: That’s amazing!

Ferrari: Except my heater.

[Laughter]

Ortner: Except the heater.

Ferrari: Yes. My –

Ortner: That’s amazing. What was in the basement that could have been ruined that wasn’t?

Ferrari: Well, it’s an earth floor basement, so there were – we didn’t really have anything down there.

Ortner: That’s a miracle.

Ferrari: There were some –

Ortner: That it occurred in the basement and not elsewhere.

Ferrari: Yes.. There were canning jars down there so –

[Laughter]

Ortner: No longer edible!

Ferrari: They can be washed. But, yes, so I just, you know, there are points in time where I can feel hopeless, just like any individual that has a major thing happen like loss. But I keep coming back to, you know, something that’s bigger than me and saying, “Okay, this is, you know, I have a – ”

Ortner: A job bigger than you. You mean a task that you’ve been assigned.

Ferrari: Right. Step up and sort of, like, let myself fall apart at certain points in time, but not very often. Not, you know – now it’s time to put one foot in front of the other and go forward. Dan and I used to talk about putting one foot in front of the other.

Ortner: Day by day.

Ferrari: Yes. Because running a business that’s an alternative business for 30 years – it was – that was its own challenge. So I’m used to challenges.

Ortner: When you say alternative, what do you mean?

Ferrari: Alternative meaning, we are, you know, we never knew, we had no –

Ortner: Where the next cent was coming from?

Ferrari: Right. We never knew where – when regular income was happening.

Ortner: Mhm.

Ferrari: And the first year or so –

Ortner: That’s really like surfing.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: Balancing

Ferrari: Balancing. A lot of balancing.

Ortner: Takes a lot of emotional stability.

[Laughter]

Ferrari: Yes. And I remember the month that happened early on – we were still in our 20s – and no jobs were at the shop at that point in time. Because we would do also printing for other people.

Ortner: What kind of printing were you doing? For cash, that was coming in?

Ferrari: We were –

Ortner: At the time.

Ferrari: We were printing books. We were printing limited edition books for small publishers in New York and the United States.

Ortner: Were you printing artwork also?

Ferrari: We did mostly the type. We sort of specialized in casting and making letterpress type – typography. And we were learning and perfecting our skills at the time. And I remember we – Dan and I – had a conversation back then and we were – it was – that was 1982. And I remember saying to each other, “Well, we can either get a job, like, outside of this and then have this be our art, or we could just plug in and do this and really learn it. Learn it deeply. And teach ourselves and be just doing it. And then doing our own book in addition.” That’s what we decided to do.

Ortner: That’s a hard decision. A brave and courageous decision when you don’t know where the next cent’s coming from.

Ferrari: Yes. We didn’t always know. So the first month that we had no income at all, Dan was like, “Oh, what are we going to do here?” And I said, “Don’t worry.” I said, “I have food in the pantry. I have pasta.”

[Laughter]

Ferrari: And we just didn’t worry about it. We just sort of said, “Okay. We’ll eat from the pantry,” and then by a month, some stuff came in again, we had some work, and that went on for 30 years. You know, I mean it got better over time and then – but it was up and down, always.

Ortner: Do you think it makes a difference if you believe – you know, there’s so many books written lately that say, “If you believe and expect the best, it will be coming your way.” What do you think of that idea?

Ferrari: Yes. I think that is true definitely to – because your attitude – I think it affects your attitude. There’s always going to be things that are difficult. And it’s the getting through the difficulties that – and how you approach it – because you can have the worst thing happen to you imaginable and yet you can still – you can survive that and you can be – it can strengthen you and you can actually still be – find happiness and joy in the world and still be – have the worst thing happen.

Ortner: Don’t you think, though, that you become a different person in order to survive that?

Ferrari: I think, yes, I think you –

Ortner: Will pull out elements of yourself that you didn’t even know you had until your back was against the wall?

Ferrari: Yes, I do. I think so. I think, because I remember having something happen at one point in my life, and it was very difficult and yet realizing – and going through such a stressful time – but then realizing and saying to people, “But, you know, despite it all, I’m still cheerful.” And it was true. And I was like, I didn’t expect it. I thought that, like, if you had the worse things happen in your life, it would crush you and I think, from living a life where there was uncertainty and difficulties that I had weathered enough to somehow find that I could weather something really difficult and yes, have it affect me and not always be happy but still, overall, find something to be cheerful about, kind of, somehow. So you know, that was – that was my experience and then – so losing my partner, I’d have to say that was the – that was the big one. That was not expected. So I guess I’m lucky that I had had a life of challenges, because I was hopefully meeting this challenge, you know?

Ortner: It sounds like you are. What do you feel – well, you’ve actually answered what life has taught you so far. What are you thinking now in terms of goals for the present and future in your life?

Ferrari: Well, I think one of the things I was thinking about is I have goals and I have also themes.

Ortner: What do you mean?

Ferrari: I think – almost try to think in terms of themes a little more than goals, probably.

Ortner: That sounds interesting.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: Themes.

Ferrari: Themes, like what’s – because goals sometimes can – things can get in the midst of things.

Ortner: Sure.

Ferrari: And pushed back. I think Dan and I used to think in terms of this other idea – this other way of thinking of – having themes. I remember doing a radio interview many years ago with, oh, I think, when we first started the press in New Hampshire. Talking about the theme of oneness, of having everything be integrated in our lives. Like the Press was not just our work. It was like our life that – we did those things, but it was also our art and our poetry and this whole thing came together to be a one – a singular unit – and everything was equally important. Even the garden was a way that was something that was part of that parcel of things.

Ortner: Did you grow your own fruits and vegetables in the garden?

Ferrari: I did the best I could, actually.

[Laughter]

Ortner: I think we all do.

Ferrari: You know, the Press isn’t a village. It’s a tight little space in the village, so I don’t have – I’m not out with acres and acres of land for gardening and growing. But it was a little important part of my life too and still is. When I’m stressed, I’ll go out in my garden, you know.

Ortner: Very meditative.

Ferrari: Yes. It’s important. You know, I’ll go out and listen to the birds. And that will affect my poetry. Or I’ll go for a walk in Pisgah wilderness and that will affect images, you know.

Ortner: So I take it you’re still writing prose as well as poetry and are you still creating art?

Ferrari: I’m still writing. I’m still an artist. I haven’t created much art since losing Dan. I remember thinking that, of all the things that I had to do to –

Ortner: Sustain.

Ferrari: To sustain, but to make sure that I fulfilled or filled the space that Dan had been in. That I needed to, that I wanted to do. The poetry was not one of them, I felt. I said, “Okay, Dan’s done that. He’s – I don’t have try to fill those shoes.” But that was the one thing that I couldn’t stop doing. I was just writing, writing, writing. So I’ve been doing writing instead of doing visual images. Although I’ve done a few visual images lately.

Ortner: Are you writing poetry as well as prose?

Ferrari: I’m doing both. Yes.

Ortner: Now, what made you get involved with VermontViews.org, where I originally saw your work?

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: Did you meet Phil Innes or…?

Ferrari: A friend of a friend introduced me and I decided that – I was writing poetry at the time, like, just baskets full because of the inspiration of where I was in my life. Emotionally. Phil said something about an article, you know, about writing articles. And I said, “Yes, I think I’d like to do that.” Because there’s something – something different you can do in prose to write about your thoughts.

Ortner: Yes, it’s very different.

Ferrari: Yes. And I wanted to write some of these thoughts down.

Ortner: Is that new for you, to be moving poetry into prose? I know it’s new for me.

Ferrari: Yes, I’ve never really written much prose, written articles or anything like that. But it seemed, you know, to be a good challenge.

Ortner: Your prose, though, that I’ve read, is very majestic; it’s very poetic. It’s really deeply moving. There’s nothing flat and matter-of-fact about it. Would you be willing to share some of your work with us?

Ferrari: Yes, I could. You mentioned you wanted to hear a little bit of the piece I wrote for the very beginning.

Ortner: Well, this is the piece that originally affected me so profoundly, so I wanted Julia to share it with our audience.

Ferrari: Okay. And I’ll read slowly. So this is from the first article in VermontViews, and it was called Between. The article itself – the column, rather – is called In Between and that relates to the fact that – first of all, the village that I live in is Ashuelot and that is Algonquian for the word ‘between.’ So that came up and I also read that Golgonooza, the name of my business, also has to do with a place between in the mythology of Blake.

Ortner: Oh, that’s interesting. Two things that have to do with in between.

Ferrari: Yes. I felt like I was in a place that was in between too, because I certainly wasn’t where I used to be. I was not where I was going yet and I’m still not there yet. So I’m in this place.

Ortner: And we don’t know where we’re going.

Ferrari: That’s right.

[Laughter]

Ferrari: So I’ll read just a little bit from that first passage in the middle of the work:

I have had the chance to experience this world of between deeply through loss. Tonight, as I walked in my backyard, I saw the light on and saw inside, in my mind’s eye, the past that existed before everything in my life changed. A life that had stability and purpose, joy and simplicity. The place remains the same; the light that shines outside that same window is no different. But what I briefly saw is the past. Am I somehow suspended between two worlds: the past and the future? The world speeds by while I hold the transitory in my hand, looking at it, trying to understand where it has gone. When we lose someone we love deeply, the world changes and we experience everything in a kind of slow motion from the rest of the world. We are in this world but not of it. Things that once seemed important to us no longer are. A kind of silence surrounds us as we stand with one foot in this world and another in the invisible world of the soul. The physical world and the spiritual world coincide in ways they have not before and the depths of the universe opens into us like a funnel, pouring the stars through our heart. In these moments of being between certainties, when we are neither in the future nor the past. What time and the motion of the universe takes away from us becomes a pathway through the darkness to a new beginning. One that we face with either a trust and an anticipation of the rich possibilities ahead or a path we fear because it is so unknown. I think allowing the kindness to relinquish our need to define the future with absolute certainty and not pursue that constant need to assure ourselves that we must have all the answers before we act. Rather, to live with the uncertainties of the moment, for the time being, while we are in the world between the known.

Ortner: That was very beautiful. Was that the first piece that you wrote or just a piece I happened to chance upon that affected me so profoundly?

Ferrari: That was the first one. Because it said I begin this column with the concept of ‘betweenness.’

Ortner: Ah. And the idea of being in the world and being in between and the idea of everything slowing and realizing that you can’t predict any certainties for the future, so how are you going to face that unknown that you’re – you’re actually in the unknown. The in between is the unknown as well as the future.

Ferrari: Right. Yes. Because you’re in this place – there are these places that exist in our lives, in everybody’s life, where you – where things change and you’re in transition and so I think that that’s this concept of ‘betweenness.’ I was certainly in and still am in a place of transition. I noticed that a part of me wanted to be stressed out or wanted to be, like, thinking about, “Where am I?” You know. And “Where am I going?”

Ortner: Right, you mean you wanted some certainty. Some definition, some boundaries there. Like what might point to where I’m going.

Ferrari: Right. Of course I couldn’t know that.

Ortner: I think that’s a normal, you know, you want – you were grounded in a particular way. The ground has literally been pulled from beneath your feet; you are in transition, floating. I think we’re accustomed to thinking if we say, “Number 1, I’ll achieve this. And then that will lead to this, cause and effect.” You begin – you want to think that way, but you realize that you’re really floating. You have to acclimate yourself to that understanding that you actually, in reality, are floating. You are in transition. You haven’t touched a different ground and you can’t return to the old ground except in memories. And the image of the light in the house, I think also, was a very chilling image, you know, because you look at that house and yes, the light is still there, but the light that was in the house is no longer there.

Ferrari: Right. Yes.

Ortner: Just the objects and the light and that’s, you know, my hair does kind of stand on end. It’s like looking in at your own life as if you had stepped outside of it and you are an observer. I think, you know, I can remember also, many times as a child, and even in my 20s, at a funeral, being in the funeral car and looking outside at people walking on the street and it seemed like there was not just the pane of glass of the car that I was in between me and those people going about their ordinary, normal, schedules on the other side. But it seemed like an impenetrably thick wall that I was feeling. A very heavy, thick, dense wall that could not be penetrated in any way. And I was on one side of the glass looking at them and could see them clear-eyed, like one of those white wolves, but they couldn’t see the grief that I was in in the dark car. The image that that sensation was very – repeated itself with many funerals that I went to. Over and over again. In a way, that is what it feels like, because when you are in that abyss – you’re in that dark place – everything does seem slower and you see the world in a different way. It’s like you have a different pair of eyes almost.

Ferrari: Yes. And –

Ortner: Although others don’t look in at you and that’s what’s so strange.

Ferrari: That’s right. Well, they don’t see that you’re in a different world.

Ortner: No, they don’t see, you said you’re half in this world and half in another and that’s what it is. I think that’s what happens. I think it’s when people are in terrible grief for a good reason or crisis and something happens unexpected that’s totally crushing. That’s when you leap from being totally absorbed in the material world to floating in between the spiritual and material world. That’s when the soul becomes most raw and evident.

Ferrari: And I think what I observed was that that place of in between that’s so uncomfortable or can be uncomfortable is a place that you have to just be in and not try to jump and leapfrog over it and be in the future. Because it’s this – you’re there and it’s – it doesn’t happen very often and you have to almost be there and make use of it and – because it’s there for a reason – it’s part of that movement into something new. It’s almost like a place where you’re formulating into a new person, somehow, that there’s – You know, it’s almost being able to float, as you said the word float, and not be totally involved with planning and all the things that we do. That we have to nail it down and know exactly what we’re doing. But to allow ourselves to be in a place that’s uncomfortable, that’s –

Ortner: Very uncomfortable.

Ferrari: Unknown.

Ortner: Because it’s so unknown.

Ferrari: Yes. I think, when you do that – you – all the possibilities of the future, which are open at that point, can actually happen. Instead of planning and making things happen, things that are just unexpected can happen if you’re open to them. So it’s being open.

Ortner: Who was the writer that said, “God’s way – coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

Ferrari: Mhm. Interesting. Yes.

Ortner: Coincidence. When you meet someone, an exchange that occurs, a face that you see, an image that comes to mind that you catch onto. For myself, I know periods of transition and pain that I’ve been through, very similar to the one you’re describing, felt very raw, but also, everything in the physical world, especially in nature, became extremely vivid. I remember, after my divorce, not being able to sleep through the night and watching the dawn come over the mountain in the Winter and seeing when there was ice – drops of ice that were frozen on the trees, of course, that were leafless, and the forest surrounding the house and they looked like millions of shining diamonds.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: Like I was surrounded by diamonds and it was something that, under ordinary circumstances, I wouldn’t have been up all night, I wouldn’t have seen the sun come over the mountain, and I wouldn’t have seen the millions of diamonds.

Ferrari: Yes. I had a – also had a distinct perception of nature too, after Dan’s death. It almost was – felt that when I would look at nature that it was excruciatingly beautiful.

Ortner: Yes. Right.

Ferrari: And that that was part of what had happened. That was part of what happened, this opening to this experience in life, which is death. That we so shy away from. That is – that there was a sharpening of my awareness to the natural world.

Ortner: Now I felt that that previously, I had seen, it sounds funny, but, it’s almost like I had viewed the natural world as a beautiful picture postcard that was in the background as I went about my business and all of a sudden, I became part of it. Part of this immensity that was absolutely beautiful and I was just a small part of it.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: A particle, a little particle.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: But not separate from it any longer.

Ferrari: Right. Yes, I can understand and relate completely to that. It was a very powerful experience. I would look at certain immensely beautiful things in nature and it would just bring me to tears, because it somehow connected me to the depth of this life, my life, my connection to my partner.

Ortner: And what a miracle it is to be here, just be alive at all.

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: In spite of the trials, travails, the losses, the conflicts, the ills, and you know, what we experience moving through life. It’s so interesting because there are very few writers who consider themselves, I guess I mentioned, spiritual psychologists, but there are a handful for – I’m thinking of James Hillman. I’m reading some of his books lately and he speaks of the idea that perhaps we’ve all made contracts before we were incarnated into this physical form. And we’ve decided what are the lessons we need to learn this time around. And chosen perhaps a particular circumstance, our lovers, our husbands, our mates in order to work through what we need to to move a step higher on the spiritual ladder. I think that that’s something that, I mean, I myself did not think of that certainly at the time of my divorce or other losses. But then, after a period of months or years passed, and I realized I’d become a different person. And found qualities in myself and a beauty and life that I had never even imagined witnessing before. It was like a door to light had opened that I never knew existed and I had somehow walked through it and come out on the other side.

Ferrari: Well yes, we can either look at the everything that happens to us as something sort of attacking us and having sort of bad things or we can look at, you know, we have two choices.

Ortner: Well, we have that choice. Yes. Which is the better choice as far as our own growth? We do all have that choice at each moment. We can blame circumstances, parents, lovers, husbands, the people around us, relatives, or we can just look at and say, “Hm. These people are doing the best they can with what they know at the moment and so am I.”

Ferrari: Yes.

Ortner: And that’s the best we can do right now. Yes, you can look back, and say, “I might’ve done it differently.” If I could go back ten years, of course we all would have made a different choice, because we’re wiser now. Or more knowledgeable. But we can’t go back and neither can the people around us go back. We’re all doing the best we can. And it’s like we’re all walking across this bridge of life and everyone is carrying their own baggage. Not everyone is going to yak to you about their baggage, how heavy it is, and complain and whine and snivel and tear their hair out. So you’re not aware of what baggage other people are carrying unless you’re very close with them and they confide in you.

Ferrari: Yes. Well, I was wondering – yes, I agree – I had a moment where I was fixing, you know, picking wood up off the ground that had fallen from my wood pile that had somehow, you know, fallen over and it was a rainy day and I was picking it up and I noticed I could’ve really enjoyed that sort of damp sort of drizzle or I could’ve – but you know, instead I was sort of like, kvetching to myself about, how come nobody’s helping me?

[Laughter]

Ferrari: But I wonder, on that note, would you like to hear a poem?

Ortner: Very much so.

Ferrari: I have brought a couple.

Ortner: Whatever you can share with us, that would be great.

Ferrari: Okay. This poem I’d like very much to read. It’s called A Place of Brilliance.

Ortner: A Place of Brilliance?

Ferrari: A Place of Brilliance. It’s a poem that relates to a dream that was told to me and also being in part of my village in Ashuelot, up on a hill, one day, all by myself and having the pine trees getting blown by the wind and listening to that. So it’s called A Place of Brilliance.

Today I think about your journey

Imagine the things you have seen

How nebulas spiral through pale starlight

Like DNA, forming the color of a baby’s eyes

Through rivers of rain and unmoving ice

Shimmering sand and unrelenting heat

Valleys of deeply scented flowers stained the color of saffron

You travel

Dark starless nights

Cold, blue, translucent oceans

Universe within universe

It opens around you

Catching the wind as it tunes the pines

Gathering their voices into a chorus of whispering breath

I remember you dreamed you were in a place where everything was white

A place of brilliance where even our black cat

Who was there waiting for you, had become new again in white

Six days ago, on the day that marked the last day of your life

The sky wept and the winged ones, the finned ones, the four-legged ones

Plants and animals

All the beings of the Earth

Wept for you as the rain and thunder flooded from the sky

Ortner: That is beautiful. I’m glad I’m not reading.

Ferrari: For Dan Carr.

Ortner: That is just incredible. Incredible.

Ferrari: Thank you. Let’s see… Would you like another one?

Ortner: Definitely.

Ferrari: I have another one, two others. One called My Odysseus. Dan used to read the Odyssey and Homer. It amazed me because he’s reading these amazing works and of course, I was not reading them. So I decided after he died, that I was going to pick up the books that he was reading and I was going to –

Ortner: So you’re reading the Odyssey?

Ferrari: Yes. I was reading the Odyssey and I’m reading it and I realize, “Wow, this is about loss. This is about – ”

Ortner: A journey.

Ferrari: Yes. A journey. And it’s about the same things I’m going through. So I wrote a poem about it. It’s called My Odysseus.

I wait, holding my heart away from the suitors

Wait for my Odysseus, who is away on the sea

Far from my shore

I weave my heart by day and unwind the threads by night

In order that time will slow

And you will return from afar to my door

I look to the road each day

Listen for your steps

Await your call

That I may dance with you again

Once we walked the long road together

Forged the strength of our lives

Today, I drink from the cup that we drank from together

Remember the sounds of the river fall through the seasons

Knowing that the wait will be a long one

Like Penelope for her Odysseus

I wait for the hours to bring all that endings and beginnings have in common

Ortner: Mm. I think you have about two minutes. Do you have time to read another one?

Ferrari: I have a short one.

Ortner: Because they’re so beautiful.

Ferrari: This one’s called What’s Not Here and it relates to Rumi’s poem and it has the quote from Rumi, “What not here, emptiness, I only know what’s not here.” Rumi.

Emptiness

That word arrives again

Like the word loneliness

It contains so much, claiming to hold so little

Remnants of people and things

Memories held in motion, held in pages that turn

Our past so alive I can touch it

Two birds dart through the rain by this window

Landing in a whirl of gold as the trees dance once again in costume

Before all falls to Earth

Ortner: “As the trees dance once more in costume before all falls to Earth.” You have been listening to Write Action Radio Hour and we have been lucky enough to have Julia Ferrari here. If you just came in, I’m putting this on the archives on a flash drive and hopefully, we’ll be able to have a CD made of the show. We’re very lucky to have Julia here and I’d like to thank you very much for making the journey to Brattleboro. And coming on the Write Action Radio Hour and I hope we can get you to come back again. This is the first time I’ve had the privilege of hearing your poetry.

Ferrari: Thank you.

Ortner: I’m not familiar with your art. I was intrigued by your prose, but now I’m even more fascinated by the poetry, which is very, very deeply moving. Just one last question: are you planning on putting a book together of your own poetry and art?

Ferrari: I am hoping to make a book of these poems written in response to losing my partner.

Ortner: Will that be called In Between?

Ferrari: No, I’m working on a title and thinking about a design. So that part probably will come – the title, you know, will come as it comes. But pulling together the poems, writing some more and then eventually designing the book and making art for it.

Ortner: That sounds quite incredible. Thank you much for joining us. Again, we’re coming to the end of the Write Action Radio Hour. This is WVWLB in Brattleboro 107.7 FM, your community radio station. It’s almost 6 o’ clock. And again, I’m reminding you all to go to the Brattleboro film festival, 10:00 the 31st to 11:00 the 9th and the Boston Gay Men’s Chorus will be at the Latchis Theatre, November 1st. Thank you again for listening and please listen next week to Molly Malone on the Write Action Radio Hour. Have a great evening and thank you so much for joining us.

[Music]