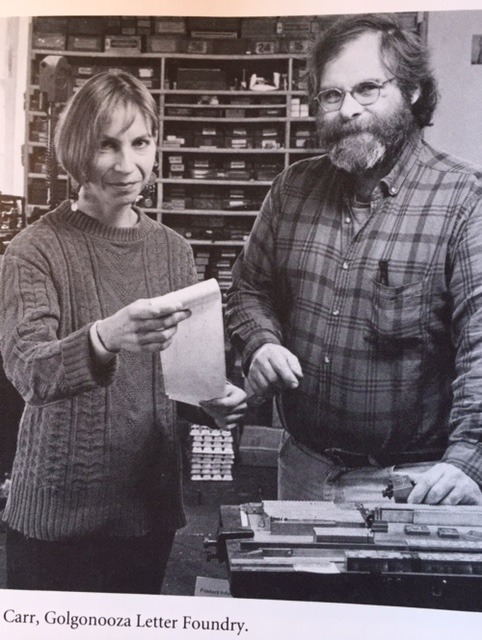

Ashuelot’s Julia Ferrari and Dan Carr turn passion into art.

From

Posted: Saturday, June 5, 2004 12:00 am in the Keene Sentinel

By Will Coghlan

Like something out of a limerick, they are two artists from Ashuelot whose names fit together for a piece of clever, if tired, word play. She’s Julia Ferrari. He’s Dan Carr.

“It took me a few years to see that one,” Carr says, of their automotive last names. “Most of our friends were way ahead of me on that one.”

As business partners, creative collaborators, and husband and wife, Carr and Ferrari share a number of passions that first brought them together years ago. Ferrari is a painter, printmaker and book artist, specializing in abstract painting. A series of her work, “Further Mound Series,” is on display at Bagel Works Cafe on Main Street in Keene.

Carr is a poet, writer and printer who recently embarked on a new endeavor — politics. He’s running for a seat in the N.H. House of Representatives.

Ferrari and Carr have lived in a long, two-story brick building on Route 119 in Ashuelot for 22 years. The first floor of the building is a big, open space, filled with the tools of the book-making trade: printing presses from various periods, racks of type, stacks of handmade paper, and pages of elegant lettering and illustrations, ready to go into a book.

In the darker corners of the print shop, medieval-looking machinery lurks in the shadows, waiting to be called into service for some largely forgotten part of the process.

They call their business the Golgonooza Letter Foundry, a reference to the “city of transformation through art,” found in William Blake’s 19th-century poetry, Ferrari said.

The birth of a business, the re-birth of a village

Twenty six years ago, Carr was living in Boston, working with a few partners in a printing business called the Four Zoas Press (also a Blake reference). Along with mastering the trade of printing books by hand, he was a fledgling poet, struggling to find a forum for his work.

“There were something like 180 million people in this country then, and only 20 or so new collections of poetry published each year,” Carr said, lamenting all the good writing that was going unpublished.

He knew other writers were experiencing the same thing, so he put a notice in the back of an alternative newspaper called The Real Paper, advertising a class to teach writers and poets how to print their own books.

Ferrari signed up, and was one of the few students who stuck it out until the end of the course.

“Julia was one of the dedicated folks,” Carr says.

The printing and bookmaking was a fitting complement to Ferrari’s primary artistic passions. A painter since the early 1970s, she studied Art History and Studio Art at Mount Holyoke College, where she received her degree.

Through friends in the Monadnock Region, the two found the empty building in Ashuelot, and with surprisingly little deliberation, they made the move to the tiny village beside the river.

“We made the leap,” Ferrari says with a laugh. “We were in our 20s, and we didn’t really think about having a business out here, with no contacts. Had we been in our 40s, we might have been more careful.”

When they moved to New Hampshire, Ashuelot was a nearly abandoned stop on the road between Hinsdale and Winchester. A textile mill had thrived there during the 19th century, at one point manufacturing woolen blankets for the Union Army using power provided by the river.

In 1916, the village buildings and property were sold off in parcels. But the industry foundered and the mill closed in the 1940s, so when Carr and Ferrari moved in, the village appeared much as it had 75 years earlier.

There were three or four “old timers,” Carr said, two of whom had been born in the building where the letter foundry now operates. Through the local historical society, they found one of the brochures published when the village was booming — a real estate ad touting the chance to come purchase a plot near the mill.

“That was one of the richest parts of moving to New Hampshire,” Carr said. “Nothing had really changed in our building until we moved in, and we had people coming over to tell us stories about what it used to be like.”

Today, Carr and Ferrari feel deeply rooted in the little village. It helps that there are a few more neighbors now.

“More and more people are taking an interest in improving the town,” Carr said.

Learning all that her paintings have to teach

Ten years after moving in and starting their business, Carr and Ferrari got the chance to purchase the building next door. The white, two-story structure once operated as the mill’s store, and the open spaces of the glass-front first floor makes just the right studio for Ferrari’s painting.

When Ferrari displays her work, there is always one “seed piece” that will never have a price tag dangling from it. Dozens of paintings can spring from that one work, and it’s often the inspiration for her next series, too.

As an abstract artist, Ferrari says her work includes both dream scenes and elements of reality — series of dozens of works that fit together to form images she sometimes describes as “diary entries.”

“The seed piece says something to me that I can get inspired about for the next series,” Ferrari says. “I haven’t stopped learning from it yet.”

Ferrari’s paintings have been shown throughout New England, including in galleries at the University of Massachusetts, the Vermont Studio Center, Keene State College and Plymouth State College, where she was selected as one of six Granite State artists for the inaugural show at the Karl Drerup Fine Arts Gallery.

The University of Alabama hosted a show of both her paintings and book art.

The books she and Carr have collaborated on are scattered to the far corners of the globe, including in university libraries at Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Dartmouth and Brown, Smith College, Wesleyan University, the Hague and St. Brides Library in London.

One of their recent projects was a commission to print a book of poetry by Maya Angelou, complemented by etchings of jazz musicians by artist Dean Mitchell. Jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis composed music to go with the project.

When they went to New York City to celebrate the book’s publication, they were treated to a party in Harlem, dinner with Angelou and an impromptu performance by Marsalis, who leaped to the stage to accompany the jazz band.

For a book of Carr’s poetry, “Gifts of the Leaves,” Ferrari created unique “monotype” paintings to grace the first page of each of the 26 original copies of the book, which contains 26 poems — one for each letter of the alphabet.

In a painstaking process measured in thousandths-of-an-inch, Carr designed, carved and cast an original typeface for the book, naming it Regulus, after a star in the constellation Leo. Carr says the capital “R” is his favorite, although the “Q” is the most eye-catching, with a fanciful, over-long tail extending out into space

Carr says he is one of only two people in the U.S. who still practice the art of designing and hand-crafting unique new typefaces.

The books created at Golgonooza deserve a word more eloquent than the simple title “book.” Held in sturdy, cloth-covered boxes, they are elegant and artistic endeavors. The stark, black letters are spaced sparingly on the heavy, handmade paper. Small squares of Ferrari’s art are scattered among the pages, each protected by a delicate sheet of tissue.

“We like to develop our arts in parallel,” Ferrari said, even though she points to opposite sides of the studio when asked if they work in close physical proximity.

While the poems could exist without the art, and the art without the poems, the combination of the two makes for a stunning presentation.

“Julia’s art is no more an illustration of my poetry than the poems illustrate her art,” Carr said.

Finding inspiration, evolving advocacy

Just west of Ashuelot village, there are 14,000 acres of wild forests, trails, rivers, ponds and wildlife that have served as a source of inspiration for the artist and poet over the past 20 years.

Pisgah State Park is a sacred place to Ferrari and Carr, so when changes in park management this spring prompted fears that the park would become less wild, and less protected, they found themselves stepping into the role of public-lands advocates.

Ferrari organized a forum one April night in her studio to discuss the threat of development in the park. More than 100 people showed up, and she now volunteers her time as the head of a new group called Pisgah Defense, working to advocate responsible park stewardship.

“Even though it can be tough to find time in the schedule of a business owner and artist, we feel committed to those things,” Ferrari said.

Carr has begun to campaign as a Democratic candidate for state representative, based largely on a conservation platform. And of course, he’s printing his own campaign signs — campy white lettering on a vintage green background.

“For us the park is a primary source of inspiration,” Ferrari said. “We believe in the public’s right to have quiet, natural places. If we lose those things in our push for progress, what else is there left to do art about?”